I grew up in Lake Orion, Michigan, a suburb of the massive Metro Detroit urban sprawl. If you didn’t own a car, you were a loser. Yet, the city I call my hometown was once a train trip to Detroit and it used to be a vacation spot for wealthy Detroiters. The town was a resort, and people walked everywhere. Then the Car came and changed all of that.

“When I actually looked into the history record, documents from the time, I found just the opposite,” Norton says. “What Americans in cities wanted in the ‘20s was to get the cars out.”

Media at the time recount pedestrians ranting against the automobile as an intrusion and an undemocratic bully. Newspapers contained cartoons portraying rich drivers in luxury cars running over working-class kids. Three-quarters of traffic fatalities at the time were pedestrians.

It’s time people took back our cities and towns and demote the car to just another means of travel. The Love Affair With the Car was a marketing gimmick to shove the Interstate System down unwilling throats be convincing people that what they had believed in was wrong.

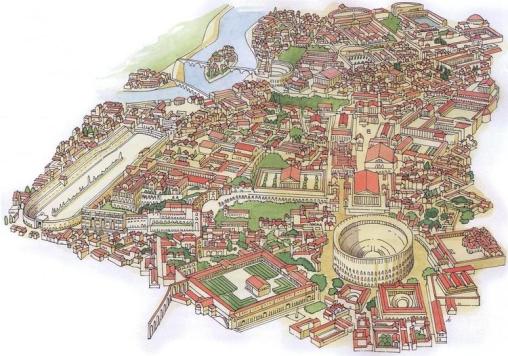

Our cities were very livable before the car, and pedestrians were the true master of the streets. Only in special districts do you see scenes reminiscent of days gone by.

State Street in Chicago, photographed in 1903 by Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Then there is this “war on cars”.

“It’s the history that gives us the assumptions that limit our choices,” he says. History reminds us the car-dominated city wasn’t the inevitable path of progress, but one path among others not taken. History also teaches us that we should be skeptical of the power of 21st century stories in the tradition of the American “love affair with cars” — like the narrative today that urban elitists who advocate for other forms of transportation are waging a “war on cars.”

There’s no war on cars, it’s a war on people. Profit before people, cars before pedestrians. Cities and towns are for people, not cars.

On the

On the

The Farmery

June 19, 2013 by kedamono

What if you could grow and sell food in the same place? What would that look like? That is the radical idea behind Ben Greene’s innovative sustainable agriculture project, called The Farmery.

© The Farmery

Considering how far our food has to travel to get from the field where it is grown in, to a retail shelf for purchase, and the amount of energy used in this process, this is one of those things that can leave you wondering what we’ve lost. Mainly our connection to the actual way food is grown and processed.

Greene and his investors envision a new way of buying food in their concept of greenhouse/grocery. It uses a collection of stacked shipping containers, vertical planters and a modular greenhouse structures. In his prototypes, Greene is already growing a significant amount of food as he tests his concept.

© The Farmery

As we live more and more in cities, the idea of urban farms is appealing, and maybe more practical if variations on the Farmery are implemented in cities around the country. Find out more about this concept at their website: The Farmery

Posted in Commentary, Factoid, Green Living, Sustainable | Tagged agriculture, conventional food, factory farming, farmers markets, farming, food miles, fruits and vegetables, greenhouse structures, retail shelf, shipping containers, store marketing, sustainable agriculture project, Sustainable Farming, urban farms, urban life | Leave a Comment »